Questions

- 1. Who/What inspired you to start Helping Hands Korea?

- 2. When and under what circumstances did you become aware of the state of human rights in North Korea?

- 3. How do you incorporate Christianity into your work?

- 4. What encourages/motivates you to continue leading your organization, i.e. Helping Hands Korea?

- 5. Throughout the years that you have worked with North Korean refugees, what moment has had the most impact on you?

- 6. What do you feel is most necessary to improve human rights in North Korea?

- 7. Would you compare your work with that of Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad? If so, how?

- 8. What do you enjoy doing in your spare time?

- 9. What about Korean culture do you find most interesting?

- 10. What are some interesting facts about yourself?

Interview:

Reverend Timothy A. Peters

Q1: Who/What inspired you to start Helping Hands Korea?

A: There's no question that personal accounts of North Koreans had much to do with the radical change of direction of our NGO to concentrate on the suffering in the northern half of the Korean Peninsula. But looking back along the full scope of the 16 years of this work, quite simply, I am certain that it was the gentle prodding of the Good Shepherd himself, who touched my heart at its very core to respond, first, to the desperate plight of North Koreans in famine in the late 1990's, then later to the 'Russian roulette' uncertainties of the fugitive life of North Korean refugees in China, and most recently to the heart-rendering cases of children of North Korean whose mothers in China have been ripped away from them when the mothers are forcibly repatriated to the DPRK by Chinese authorities.

Q2: When and under what circumstances did you become aware of the state of human rights in North Korea?

A: When my family and I returned to Korea in 1996, I'd begun to hear accounts of extreme malnutrition in North Korea. The more I gathered information, one fact became increasingly clear---in many respects, this was a man-made famine largely due to the Kim Family regime's practice of distributing food along loyalty lines, thereby depriving the most vulnerable of the population. Later, when traveling along the Sino-North Korean border to find better delivery systems and destinations for our food aid, I came across a growing number of refugees and their life stories completely shocked me. I had never heard of (nor imagined) such an all-encompassing and suffocating social system in which human rights had been so utterly extinguished as that which was described by North Korean refugees in their personal accounts of life in their homeland. Many years later, meeting and traveling with defector, Shin Dong-hyuk, about whom the new book, Escape from Camp 14, has been written, etched indelibly in my memory the utterly brutish nature of the North Korean prisons, often compared to Hitler's prison camps or Stalin's gulags.

Interviewing former refugee women who'd endured the horrors of forced abortions after the Chinese government had sent them back to North Korea also impacted me and galvanized our NGO action more than words can aptly describe.

Q3: How do you incorporate Christianity into your work?

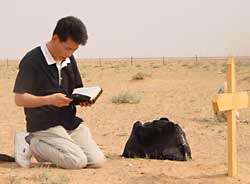

A: Well, I think in answering, I may slightly re-phrase the main point in the question. I humbly submit that it is Christ who has incorporated HHK/Catacombs into His healing work for North Koreans rather than the other way around! Perhaps we are the ones who've been recruited to find any number of ways to ease the suffering of the North Korean people. Although we are clearly Christian in our testimony, we do our best not to be coercive about our faith when encountering North Koreans for the first time, mainly in China. We also appeal to our project partners to remember that North Korean refugees are coming out of a highly coercive ideological belief system (Juche), so the great majority of them are not likely to be attracted to a pushy approach to the Christian faith. We believe that a simple demonstration of loving concern and humanitarian assistance during a desperate time of need will speak far more forcibly to them than a hard-sell approach to our faith. At the same time, for those who are eager to know more about the God who loves them, we have printed three times an easy-to-read Korean New Testament that refugees can easily put in their backpacks and study at their leisure. We also provide medicine and clothing to the North Korean underground church that is heavily persecuted.

Q4: What encourages/motivates you to continue leading your organization, i.e. Helping Hands Korea?

A: Although we don't have a constant stream of feedback, we do receive sufficient documentation to learn of lives rescued, orphaned children put into foster care, and any number of improved conditions as a result of our projects inside North Korea and in neighboring countries. Certainly, these reports constitute a major source of encouragement to us.

Q5: Throughout the years that you have worked with North Korean refugees, what moment has had the most impact on you?

A: Over 16 years, naturally there have been many memorable moments and experiences. One of them has to be the rescue along the underground railroad that was described in the TIME story "The Long Walk to Freedom".

However, none can compare to the story of Yoo Chul Min, the actual tragic story that inspired the movie Crossing in South Korea. The following is excerpted from an account I wrote not long after the bitterly sad story of this tiny North Korean refugee who, at the tender age of 10, was a victim of North Korea's manmade famine as well as China's egregiously illegal policy of forcible repatriation that caused the boy to be exposed to the harsh realities of the Gobi Desert.

Excerpt taken from article by Tim Peters "Who Was Yoo Chul Min---and Why Does it Matter?

A 10 year-old North Korean refugee boy hiding in China, became a tragic figure in a drama that was light years away from what most other elementary 4th graders are ordinarily preoccupied with--North Korean refugees' life-and-death gamble to cross the China-Mongolian border under the cover of darkness.

His name was Yoo Chul Min and his fate resulted in a heart-rending tragedy. Placed by well-meaning South Korean missionaries with five other North Korean fugitive adults, also desperate for even a fleeting glimpse of freedom, Chul Min and his companions became disoriented for 26 hours in the arid, desert conditions of the Mongolian frontier. Years of gradual malnutrition in North Korea had weakened Yoo Chul Min's body and the normal reserve of endurance and resistance to the elements one would expect of a healthy preteen boy were sadly lacking. Yoo Chul Min died from exhaustion and exposure. His body was carried across the Mongolian border by the remaining refugee team when they finally gained their bearings.

Perhaps I've taken a particular interest in this story because it so happened that Chul Min and my paths crossed in the course of my work in Helping Hands Korea. I had met and just begun getting to know this 10 year-old on two occasions, shortly before his death 11 years ago. At the time, he was under the protection of courageous Korean missionaries in the Yenbian (ethnic Chinese-Korean region) district of northeast China.

I remember noticing how withdrawn this boy was. Because he had lived in China for over a year, he did not immediately strike me as malnourished and his clothes were clean. I noticed with some amusement that he would never take off his baseball cap, even inside the house of my missionary friend. My curiosity grew into a little personal challenge to spend some time with him and see if I could find a way to break through that shell of suspicion of foreigners and get a friendship started.

I was told by those providing foster care for him that Chul Min was very studious and doing well in a Chinese elementary school. On a day in April of 2001 while visiting a fellow Christian worker's residence where Chul Min had come for the day, I happened to notice on my friend's bookshelf the Korean version of a book that I had read countless times with my own five children as they were growing up, The Picture Bible.

Despite his initial reluctance to sit down next to a dreaded American, Chul Min's curiosity about the book seemed to get the upper hand, and soon we were leafing through the wonderfully illustrated volume together and he was eagerly reading the Korean text aloud. It became the bridge for what I hoped would be a real friendship. I imagined that Chul Min and my own grandson, Alan, might become friends when he came to South Korea. Less than a half-hour later, other missionaries came through the front door announcing that Chul Min had to join others according to an escape plan that I was not privy to. Little did I realize at that time that death was only a month away for this grade school boy whose entire life seemed to lay ahead of him.

In the days that followed the jarring news of Chul Min's sudden death, despite our urgent entreaties, the security officials in Mongolia did not agree to wait for Chul Min's father, himself a recent arrival to the South from China, to arrive in Ulan Bator to identify his son's body and to be present at his burial.

Q6: What do you feel is most necessary to improve human rights in North Korea?

A: It is my firm belief that the US government, as well as the international community at large, must concentrate its primary efforts not on the North Korean programs of missile technology and nuclear weapons (as important as these are), but on exposing and eliminating the virtual slave conditions that 20 million + North Koreans live under every day of their lives. Currently, a report has been submitted to all the United Nations Special Rapporteurs dealing with human rights violations in relation to the lamentable conditions within the Hermit Kingdom. With further international pressure, a Commission of Inquiry can be formed in the UN to investigate the huge network of prisons and prison camps inside the North. Secondly, the human rights of North Korea cannot be addressed in isolation. Unrelenting international pressure, including trade sanctions if necessary, must be put on Beijing's leaders to reverse their horrific forced repatriation policy of North Korean refugees, which results in serious punishment, torture, imprisonment, at times forced abortion, and even summary execution in some cases by North Korean authorities on returned refugees.

Q7: Would you compare your work with that of Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad? If so, how?

A: Although I would hesitate to compare myself with Harriet Tubman and other great figures of the American underground railroad, I suppose there are some similarities. Certainly there is a similarity between the people being rescued: the slaves of the American South and North Koreans who have been utterly deprived of all human rights, even the right to food security. Certainly, in both cases, a secretive volunteer network has been largely responsible for spiriting those yearning for freedom and safety: the North Korean refugees being helped to safety outside of China and to other surrounding countries in much the same way that slaves were helped from town to town until they reached the free North. In the 1850's and 1860's, volunteers along the underground railroad were typically inspired by their Christian faith, and this is very often also true in the modern day network of volunteers that helps North Koreans outside their own country reach safe haven.

Q8: What do you enjoy doing in your spare time?

A: I love reading on a wide variety of topics, walking 10 km a day (with my wife whenever she can be persuaded!), and when I can find an inexpensive golf course, enjoy a round of golf!

Q9: What about Korean culture do you find most interesting?

A: As much as I enjoy Korean food and other pleasant aspects of Korean culture, I am fascinated by the sheer length of Korean history, which can be traced back 5,000 years or more.

Q10: What are some interesting facts about yourself?

A: My dear wife, Sun mi, and I have been blessed with five wonderful children (all grown adults now!) and four grandchildren! This month (April, 2012) marks exactly 40 years since a Christian conversion in my fourth year of university study in Michigan resulted in a complete 180-degree turn in my life and vocational trajectory that resulted, a few months later, into my launch into overseas Christian work in the Caribbean, then South America, then Japan, Korea, and now helping North Koreans. I feel so privileged to have been called to this work of sharing the Good News, feeding the hungry and binding up the bruised and hurting in our fast-paced and overly materialistic post-modern world. Early in my new vocation, I heard a nugget of wisdom that has been a guiding star to me over the decades:

Only what's done for Love will last."